| tf-_birch.pdf | |

| File Size: | 215 kb |

| File Type: | |

BIRCH - TREE OF NEW BEGINNINGS.

Fourteen thousand years ago the land was gripped by unrelenting ice. Nature was frozen in rest, paused in time.

Still; life stirred on the ancient windswept tundra and on warmer days the reindeer scratched beneath the snow to feed on lichen growing greener than before.

The flat landscape breeding barrenness only supported trees of sallow, aspen and juniper barely a foot high yet still fully formed with branches blossoming on milder days.

Imagine the first flowers coming into being of plantain, mugwort and shepherds purse and then finally at some point a tree reaching above its usual height and forming the first woodland landscape since the ice age.

The first woodland would have been Birch:

Of withered trunk fair haired the birch.

Faded trunk and fair hair.

Browed beauty worthy of pursuit.

Most silver of skin.

Book of Ballymote 1391

The above ‘kenning’, written down in 1391, stretches back to an earlier oral tradition which was not informed by the science of palynology

( pollen analysis) , but by the oral memory of our ancestors who knew the landscape intimately.

They knew Birch was the tree of inception and of new beginnings in the same way they knew the Yew lived for thousands of years long before science confirmed these findings. It is likely they would have known the difference between the two birches which wasn’t confirmed until 1791 and that each had its own use.

The modern Irish alphabet letters have often been related to the trees

and in tree folklore we uncover a sacred language pre-dating Gaelic and possibly the origin of what is known as Goidelic.

A language which is coaxed into the dark speech of our ancient poets who preserved knowledge through story, metaphor and poetry. A language which takes us to the root of ancient tree folklore and is called the Celtic Tree Ogham.

In the past 25 years that I have been exploring tree lore it seems to me it is the trees of the Ogham that are the basis of much of the folklore we have connected to trees from Celtic times to now. Following a definite path through the woods, especially one that has withstood the test of time will enable us to get to the other side.

If you manage to study and work with all the trees presented in this course I believe you will have a worthwhile body of lore to further understand our most precious and important wooded landscape.

Our journey begins therefore with the Birch, the tree of new beginnings and will continue through to the Yew which is the oldest of all our British trees. This natural progression will enable the reader to learn not only an in-depth knowledge of each tree but also will give an opportunity to explore different themes to which each tree relates. The themes will include woodland and natural history, herbal lore, conservation and the poems and stories connected to the wooded landscape.

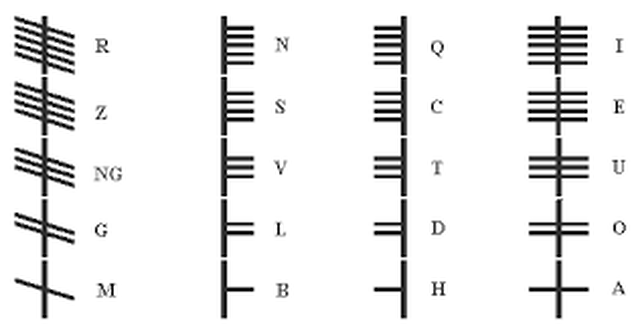

Picture below: The twenty letters of the Ogham alphabet are B L F S N H D T C Q M G NG ST R A O UE I. We shall feature fifteen of the trees in the alphabet with the addition of Lime and Beech. The other five letters are associated with shrubs (Vine, Ivy, Broom, Gorse and Heather), which we may study in another course in the future. The diagram below illustrates how the letters are written. They are a series of lines to enable them to be easily carved on stone. The stones we find carved with these letters are dated between the fifth and seventh centuries, mainly in Ireland and seem to be the names of the people that own the land to avoid any disputes of land ownership.

Still; life stirred on the ancient windswept tundra and on warmer days the reindeer scratched beneath the snow to feed on lichen growing greener than before.

The flat landscape breeding barrenness only supported trees of sallow, aspen and juniper barely a foot high yet still fully formed with branches blossoming on milder days.

Imagine the first flowers coming into being of plantain, mugwort and shepherds purse and then finally at some point a tree reaching above its usual height and forming the first woodland landscape since the ice age.

The first woodland would have been Birch:

Of withered trunk fair haired the birch.

Faded trunk and fair hair.

Browed beauty worthy of pursuit.

Most silver of skin.

Book of Ballymote 1391

The above ‘kenning’, written down in 1391, stretches back to an earlier oral tradition which was not informed by the science of palynology

( pollen analysis) , but by the oral memory of our ancestors who knew the landscape intimately.

They knew Birch was the tree of inception and of new beginnings in the same way they knew the Yew lived for thousands of years long before science confirmed these findings. It is likely they would have known the difference between the two birches which wasn’t confirmed until 1791 and that each had its own use.

The modern Irish alphabet letters have often been related to the trees

and in tree folklore we uncover a sacred language pre-dating Gaelic and possibly the origin of what is known as Goidelic.

A language which is coaxed into the dark speech of our ancient poets who preserved knowledge through story, metaphor and poetry. A language which takes us to the root of ancient tree folklore and is called the Celtic Tree Ogham.

In the past 25 years that I have been exploring tree lore it seems to me it is the trees of the Ogham that are the basis of much of the folklore we have connected to trees from Celtic times to now. Following a definite path through the woods, especially one that has withstood the test of time will enable us to get to the other side.

If you manage to study and work with all the trees presented in this course I believe you will have a worthwhile body of lore to further understand our most precious and important wooded landscape.

Our journey begins therefore with the Birch, the tree of new beginnings and will continue through to the Yew which is the oldest of all our British trees. This natural progression will enable the reader to learn not only an in-depth knowledge of each tree but also will give an opportunity to explore different themes to which each tree relates. The themes will include woodland and natural history, herbal lore, conservation and the poems and stories connected to the wooded landscape.

Picture below: The twenty letters of the Ogham alphabet are B L F S N H D T C Q M G NG ST R A O UE I. We shall feature fifteen of the trees in the alphabet with the addition of Lime and Beech. The other five letters are associated with shrubs (Vine, Ivy, Broom, Gorse and Heather), which we may study in another course in the future. The diagram below illustrates how the letters are written. They are a series of lines to enable them to be easily carved on stone. The stones we find carved with these letters are dated between the fifth and seventh centuries, mainly in Ireland and seem to be the names of the people that own the land to avoid any disputes of land ownership.

Notes on the Oral tradition.

Today we have access to so much knowledge. In a couple of clicks you can access expert information in any subject. However in the same way a plant can only assimilate so many nutrients for its optimum health, this knowledge is in danger of becoming superficial, floating around in a meaningless pool of stagnant water.

In the oral tradition every word is absorbed one at a time, every sentence contemplated for hours or even days thus giving rise to creative and original thought.

The sap of creative thought enables knowledge to penetrate our entire being to feed parts of us that will otherwise wither away like a plant which is over-fed and over- watered.

Although this is a written exploration I invite you in the spirit of the oral tradition to take the time to read each page and absorb the information to arrive at your own creative thoughts and the gifts each tree can bestow upon you.

The Birch and natural regeneration

Ancient tundra birch-dominated,

Solitude of creation, giving birth.

Naturally regenerates over thousands of years,

In the coldest of places, gentle strength perseveres.

Silver her bark, black are her branches,

A spring goddess as she advances.

Feminine power, persistent strength

Like Spring unfolding without relent.

O Birch you teach us to be gentle when we fall,

May our hearts remain open and kind to all.

J.Huet 2018

The stretch of woodland that was a sanctuary to me at the age of 12 was simply a disused stretch of land eroded by time and then perfected into the green oasis which it has now become. The neglect of land creates beauty. Glass bottles, rubbish, decaying concrete, burnt out machines are devoured in the process of time by the unstoppable power of nature often referred to as natural regeneration.

‘Nature is perfect’; this statement to me is not some romantic notion borne from someone protected in a damp proofed bricked building, with a garden of marigolds in neat rows and the weeds sprayed with chemicals, but a conclusion of nearly 30 years of living and working in the countryside, having been immersed in the untamed, unpredictable harsh landscape.

It is proven and demonstrated that when land less than 2000 feet above sea level is left to its own devices it will regenerate into woodland in as little as 30 years. On a typical fertile lowland site the process often begins with the growth of nettle, bramble and bindweed creating a tangle of plant growth that cuts and stings all who try to penetrate its depths.

Depending on the surrounding flora, tree saplings such as ash, oak, sycamore and birch find a gap in the field layer caused by grazing animals like deer or rabbit or even from more man-made materials like concrete which has helped stunt the growth of the bramble etc. The saplings start to grow and new life is formed.

On the edge of more natural landscapes such as ancient woodlands, moors or heaths, the natural regeneration will be truer to the original landscape and support a richer flora and fauna than, say, a disused industrial estate on the outskirts of a city.

The process described above is happening all the time and it does beg the question as to why plant trees? Why manage land for conservation? Why dictate a natural process impossible to recreate by a human hand? Is the conservation movement simply a man-made machine set in motion limited by the human need to label and understand the incomprehensible? The conservation model that puts trees in neat rows in plastic guards and decides which flowers grow beneath their canopy?

A natural tree is never planted, the same way as a wild animal is never born in the zoo! Tree planting is fantastic on village greens, roadsides and parks but does it have a place in the countryside at large?

Planting trees in woodlands interferes in the natural ecology of a given site, the perfected delicate balance that only nature can determine. Planted trees are more susceptible to drought, disease and can upset the balance of the natural flora.

Natural regeneration costs very little but leads to an appearance of neglected overgrown land which means it is not popular, but in the same way that rare beetles play a role in our woodlands as important as the graceful mammals or impressive birds of prey, I feel strongly and unequivocally that allowing the land to breathe and nature to regenerate will be an important step in creating wild landscapes in Britain again.

Birch is historically the first coloniser of land growing in open, more infertile acid soils producing nitrogen- rich leaves, which feed and de-acidify the soil. Birch has a shorter life span than many forest trees and is less tolerant of shade. This means it is soon replaced by trees that live longer and cope more effectively with shade.

Each tree has its own roles supporting different types of wildlife and growing in a specific habitat ideal for its needs. Before the planting of trees, each native tree had a specific region and climate that it tended to grow in, its individual genes evolving in such a way to adapt to its environment, each tree a habitat in its own right adhering to ecological laws and thus maximising the potential of diversity on its given site. To recreate this process by human means is impossible as it has been perfected over thousands of years and is specific to nature’s intelligence which is not rooted in the human analytical mind.

In early history Birch was then replaced by (1) Oak and Hazel in the north and west and (2) Pine in Scotland. In the Highlands (3) Birch remained the dominant tree. (4)Hazel and Elm replaced birch in Ireland and in south west Wales, and (5) Lime replaced Birch in the south of England. This created the five main provenances mentioned above and seven local types of tree which were Lime, Hazel, Ash, Elm, Alder, Pine and Oak. Eventually twelve main species of tree would have dominated the wooded landscape which were Ash, Maple, Hazel, Alder, Sessile Oak, Pendunculate Oak, Birch, Beech, Small Leaved Lime, Hornbeam, Wych Elm and Scots Pine. This process of evolving species colonising Britain is called natural succession ending with the most ideal species for a given area called the Climax Species.

Folklore of Birch

Our ancestors were probably more interested in the uses of trees and what their natural roles reflected and added to their world rather than their classification. The way in which folklore informs the more scientific and practical research of more modern times continues to fascinate me.

As late as the 1950s our scientific identification books were punctuated with poems, and the romanticism of plants was not yet admonished by the scrutiny of cold mechanical conservation movements or science.

It seemed after the ‘hippy’ era of the 60s and 70s the conservation movement wished to divorce itself from the veneration of nature in order to take itself more seriously when challenged by economic reasoning.

However, when the planting of conifers in ancient woodland destroyed valuable habitats as well as making little financial contribution to the economy, it became apparent that science, conservation and the veneration of nature can all grow hand in hand and even make financial sense.

Often the considerations of tradition and the welfare of individual species and habitats go hand in hand with a more viable and effective land use. The Forestry Commission has long-since reviewed its mission to create home-grown timber at the detriment of the very woodlands that provide it.

So let us explore the Birch now through the eyes of our ancestors and see what we can learn.

Originally knowledge was remembered orally as we have already explored in the form of story and poetry. It is likely these poems and stories were remembered and re-remembered at seasonal gatherings throughout the year. Skills were learnt from generation to generation and transmitted by word of mouth as the most effective way of practice.

Probably every child knew the properties of Birch for instance from rhymes, songs or stories.

In a log-burning rhyme it is stated:

‘Birch logs will burn too fast, chestnut scarce at all.’

In an old Irish story a deeper meaning is given to the burning of Birch as we enter the world of metaphor, poetry and more subtle understandings:

‘The birch as well if he be layed low, promises abiding fortune.

Burn up most surely and certainly the stalks that bear the constant pods.’

The above verse is from an old Irish tale and is uttered from the leprachaun Iubdan who speaks of the importance of knowing which trees to burn. These snippets of lore demonstrate both an intimate and respectful relationship with trees based on an understanding that we are dependent on each individual species for different reasons.

Characteristics of Birch

‘O Birch small and blessed thou melodious proud one,

Delightful each intertwining branch on the top of thee crown.’

Frenzy of Mad Sweeney 1200 Irish texts society.

‘The birch in its great beauty was delayed donning his armour,

Thou not out of cowardice but rather from its greatness...’

Cad Goddeu (Battle of the Trees) Book of Taliesin 14th-century

We now enter the world where the trees are wise old sages that can guide us through life. Their language is the deep silence and their form and movement are the expression of who they are and what they represent to us, whether it is the beauty of the spring Birch grove, the Willow bending and flowing with the waters of life or the solid old Oak giving life and protection to all that shelter under it.

The first extract above is from a poem which conveys a love of these sacred forms, in this case attributed to Suibhne Geilt, a ‘file’, an Irish vision poet who has immersed himself in the lore of the forest. The second extract is from a fourteenth century Welsh manuscript attributed to the famous Welsh bard Taliesin.

We hear in many stories of archetypal heroes and shamanic figures who finish life under the boughs of the trees obtaining the fruition of great knowledge from a well-lived life .

Gentle strength and fond love.

The Birch in folklore represents a fond love as well as being the tree of birth, initiation and gentle strength. Imagine yourself in the Birch grove allowing the flow of feelings and creative thought to arise. You see trees of silver bark and black branches, with dainty catkins and slender branches, and yet they grow in the harshest conditions and are the first to colonize. *n.b. It is important to acknowledge a tree like the Oak may well colonise a given area first but is slower growing and therefore not noticed in the early stages.

In the spring the leaves unfurl in a delicate bright green and its sap when tapped is refreshing and healing. It is discovered the cylindrical trunks of what we now call ‘silver’ birch ( Tennyson was the first to describe her thus) are ideal to make cots for new- born babies and the stiffer branches of the downy birch ideal for brooms. The tiny twigs and its bark both contain volatile oil which is perfect to light a new fire. The bark can also water proof roofs and make containers. All of these practical qualities paint a picture of a gentle tree of new beginnings, strong and dynamic and yet graceful and short-lived like the sting of young love.

The Ogham name Beithe means being, or a Being, and the Birch grove in ancient stories and traditions is a place to connect with Other-worldly visitors. This connection is further enhanced as it is said to be the first Ogham inscription that was written to warn Lugh Lamfada that his wife was being taken to faerie land.

Birch being the first letter inscription also makes sense when we also realise that the first books may have been created and written on Birch bark. An example of this is preserved in the Bodleian library in the form of the Bakhshali manuscipt dating from the 3rd or 4th century inscribed on 70 pieces of Birch bark.

The Birch is the tree of the North where the landscape is dramatic, windswept and icy cold. It decorates the great lochs of Scotland and its graceful gentle presence belies its hardy tenacious manner.

This quality may have helped our ancestors to reflect on the power of gentleness, the ability to have courage in a gentle yet persistent way. To start afresh or to begin a new venture or even a new way of being takes an unyielding strength, the strength of gentleness. For gentleness allows us the freedom to go forth at our own pace forgiving any mistakes we make.

This ‘gentle persistence’ is reflected in Birch due to the fact it was the first tree to appear after the last Ice Age, and still today has a continuous presence in the Scottish Lochs that has lasted over 9000 years.

Further south in England is a wood called ‘Birkland’ in Sherwood forest whose name implies the Vikings recognised it as a Birch wood over a thousand years ago.

Falling in love speaks of this gentleness, for it takes such courage to be tender and exposed, to trust, and allow another soul to touch your own. Diarmaid and Grainne shelter in the birch grove for protection from the jealous rage of Fionn McCuail; this is a beautiful tale of unconquerable love. As Diarmaid and Grainne fled across Ireland they built Dolmens at each place they spent the night. Dolmens are two massive lime stones parallel to each other over which is placed a third stone, the cap stone, creating a crude kind of shelter. Still today you can see the Dolmens all across Ireland which the locals still call the “bed of Diarmaid and Grainne”, bringing the passion of love into the landscape for eternity just like Birch.

These qualities are put into words in the poem below:

'While leaves were green, I gave

Veneration to my sweetheart’s leafy bower.

Sweet it was awhile my love,

To live under the birch grove,

Sweeter still to clasp fondly

Hidden together in our woodland hide,

Strolling together by the wood shore,

Planting birches together, goodly task!

Weaving the branches together,

Love-talking to my slender girl.

An innocent occupation for a girl-

To stroll the forest with her lover,

To mirror expressions, to smile together,

To live together kindly, drinking mead,

To repose together, to celebrate love,

To keep love’s secret cordon, covertly:

Truly, I have no need to tell you more. '

Anon 14th Century.

It is in the Birch grove Diarmaid and Grainne consolidate their love and begin their adventure together.

Ecology of Birch.

Mature Birch wood is often a light airy place supporting a myriad of many types of fungi (Beech wood is also great for fungus). It casts little shade and one can often observe redpolls and tits flitting and feeding amongst the canopy. These birds will use the seed as a food source and the leaves are a food source for the mottled umber caterpillar.

There are two classes of flora for Birch wood:

1. Blaeberry (Vaccinium mrytillus) rich Birchwood

2. Herb-rich Birchwoods with a grassy floor.

There are also two main species of Birch in Britain and a third species specialist to the Scottish Highlands:

1/ Betula pendula, Silver Birch

2/ Betula pubescens, Downy Birch.

3 / Betula nana, Dwarf Birch (specialist species of the Scottish Highlands).

The main two Birches were formally recognised in 1791 as mentioned in the introduction.

The Downy Birch is more associated with ancient woodlands, has stiffer twigs which do not droop (better for brooms) and leaves which have less ragged teeth and are hairy on the underside with a triangular base.

The Silver Birch is more associated with wood pasture and is more useful for timber due to a more cylindrical trunk. Its branches droop and its leaves have a straight base and are not hairy.

In Scotland and in other parts of Britain, Birch has many uses. Commercially it was used for reels and bobbins as well as the commonest fuel used for the ironworks in the weald. Locally its bark was used for roofing and making shampoo.

Herbal remedies.

Birch sap collected in March can be used for kidney/bladder stones and rheumatic diseases as well as for a cleansing mouthwash and is excellent for the skin.

Birch bark can be used as diuretic, antiseptic and anaesthetic enabling nerve endings to lose sensations and relieve muscle pain.

Birch leaves help cystitis and are an excellent diuretic, mouthwash and can help dissolve kidney and bladder stones. They can also offer relief from rheumatism and gout.

Simply dry the leaves in brown paper bags and add a heaped teaspoon to a cup of boiled water to make an infusion. Please consult a qualified herbalist before using any herbal concoction as you may have an adverse reaction to plants you are not used to.

SUMMARIES AND RESOURCES FOR BIRCH

The key theme of the birch in this course is the qualities of gentleness and strength that is needed when you begin a new project or way of being. It might be you need the courage to change difficult patterns in your life or habits which no longer are helpful to you.

Here are a few questions to actively explore the themes related to the Birch :

Do you have the courage to begin a new project or change your way of being?

Are you able to be gentle with yourself and move at a pace that will enable you to remain steady as you start afresh?

Can you honour the shy and gentle aspects of yourself and acknowledge the strength in your sensitivity?

Here are a few questions to actively explore the themes related to the Birch :

Do you have the courage to begin a new project or change your way of being?

Are you able to be gentle with yourself and move at a pace that will enable you to remain steady as you start afresh?

Can you honour the shy and gentle aspects of yourself and acknowledge the strength in your sensitivity?

|

|

|

Deepening your connection to Birch

The birch is the first tree of the Ogham, if you are able to, seek a birch tree in a woodland and make a connection with the tree.

Feel the support and aliveness of the birch grove.

If it feels right tune into the tree and ask to prune a small branch from its canopy. Make a simple wand by making patterns and carving the Ogham letter for birch into its bark (please see Ogham letter diagram above). You may wish to remove some of the bark and carve one end of the wand to a point.

Its leaves can be made into a simple herbal tea though it is recommended you check with a herbalist that it is safe for you to use. I found it a refreshing tea that soothed my joints.

Our journey with Birch has come to an end or should I say a new beginning for us to explore even further. The next tree is the Rowan who will take us further into the Greenwood and teach us more about woodland history, ecology and folklore.